dear anna

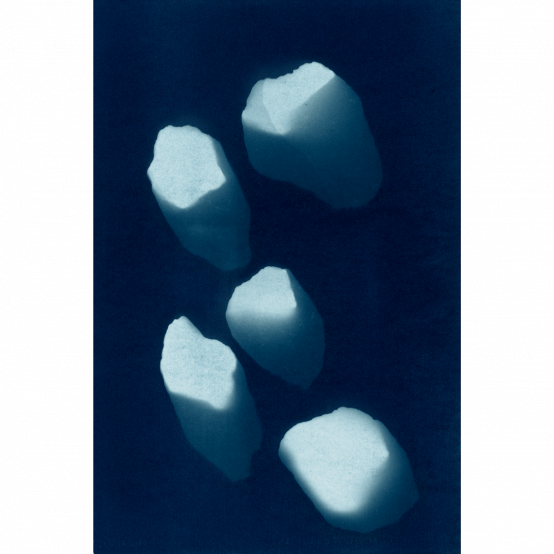

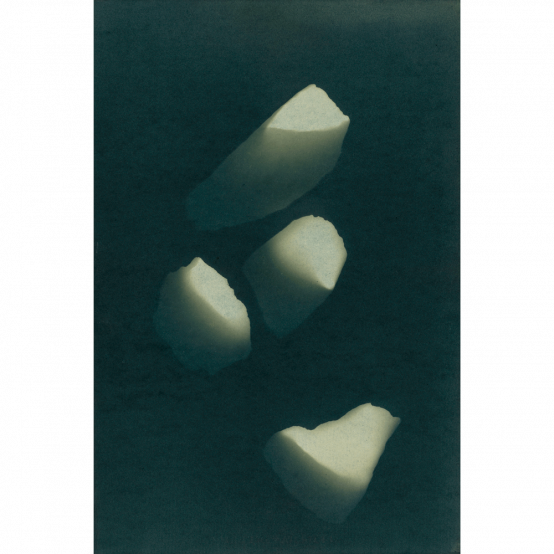

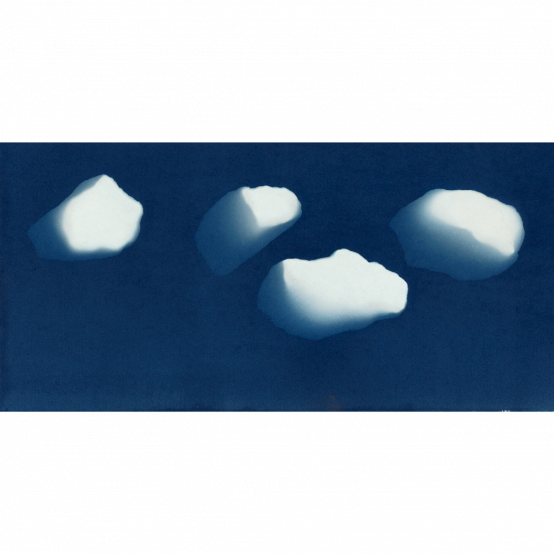

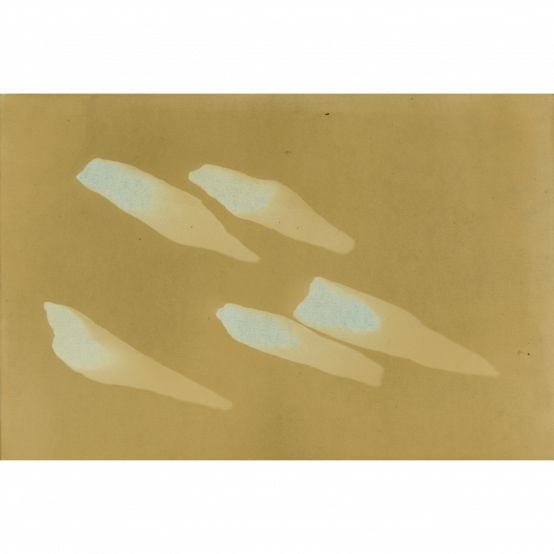

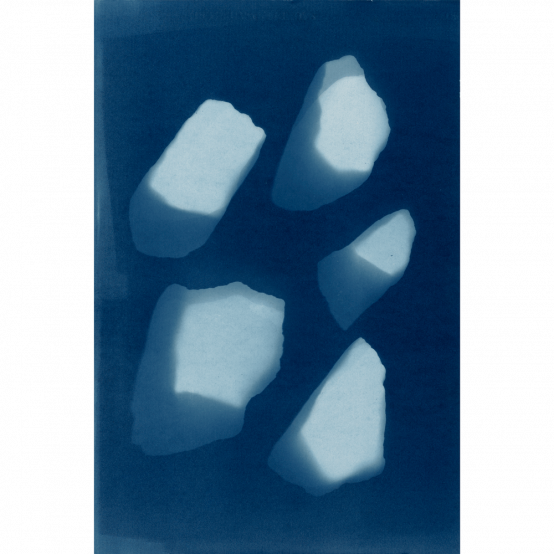

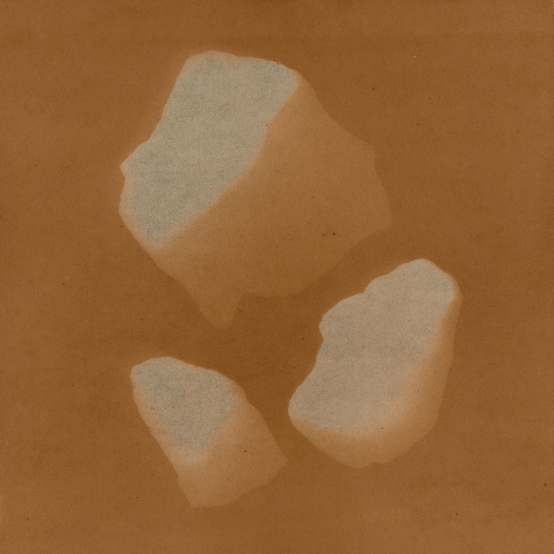

About 180 years ago, the astronomer Sir John Herschel invented an early photographic method that came to be known as cyanotype. By mixing two iron salts; ammonium ferric citrate and potassium ferricyanide, a UV-sensitive solution is created which is coated on paper, allowed to dry without light and then contact copied with negatives or objects in sunlight. The exposure is interrupted, developed and fixed by rinsing the image in a water bath and a bluescale image of archive quality appears. It continues to deepen for up to two days before it is completely finished. The method came to be used above all to copy architectural and technical drawings, hence the name blueprints.

Next door to Herschel lived Anna Atkins (1799-1871) who was a botanist and photographer and had an unusual scientific education for a woman. Her mother died when she was only one year old and she grew up with a father who was a chemist, mineralogist and zoologist. She was close to her father and even illustrated some of his texts and translations with beautiful and detailed pencil drawings. Through her father, she gained useful contacts and was admitted to The London Botanical Society in 1839. Atkins married a wealthy merchant and had no children, which gave her time to invest in personal interests, something that would hardly have happened to the same extent if she had been referred to a more traditional family life.

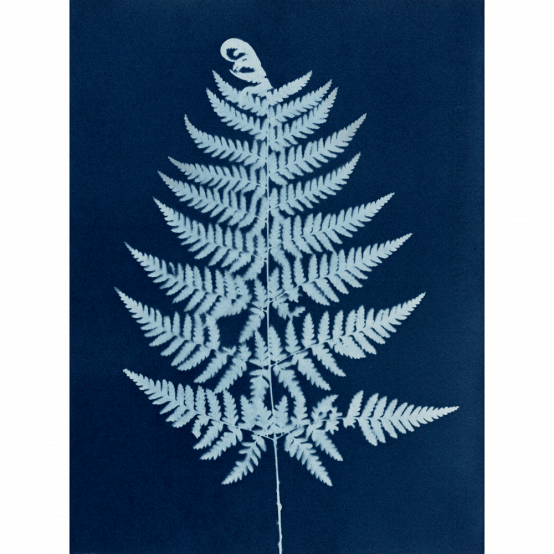

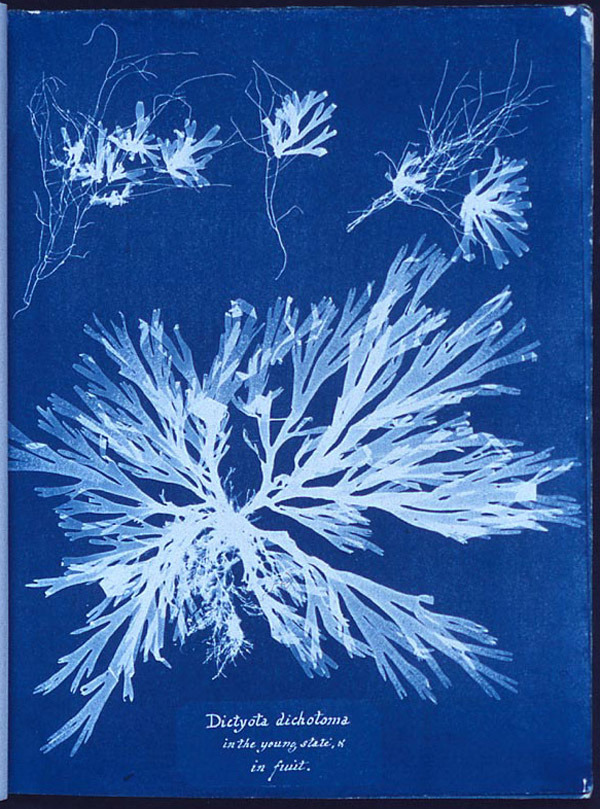

Herschel introduced her to his new blue method and she began copying her collection of algae into a composite work of hundreds of images that resulted in a book of 13 copies, Photographs of British Algae, 1843. One copy is still preserved at The New York Library and as recently as this spring, the book publisher Taschen released a large book about Atkins' work, not only containing pictures of algae but also various ferns and other cyanotype collaborations with the good friend Anne Dixon.

Historically speaking, Atkins was the one who created the first photographic book, something that did not attract much attention, probably because she was a woman. In the 1890s, a collector would write about her first book, derisively suggesting that the initials AA might as well stand for Anonymous Amateur. Perhaps the collector was bothered by the seductively beautiful images and dismissed them as banal. He was quickly reprimanded by the director of the British Museum of Natural History who believed that Atkins' photographic work had not only an artistic but also a scientific value.

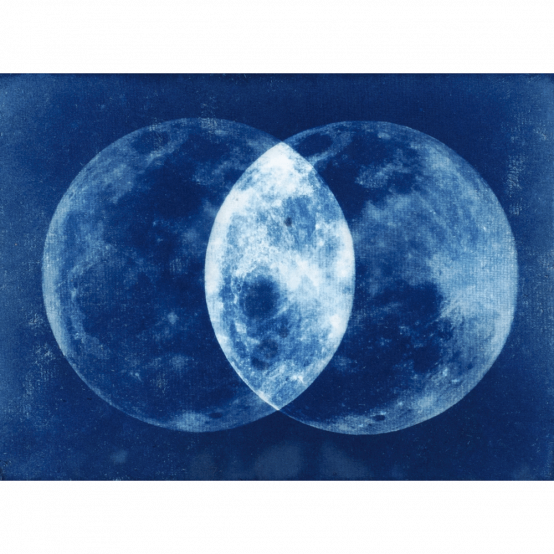

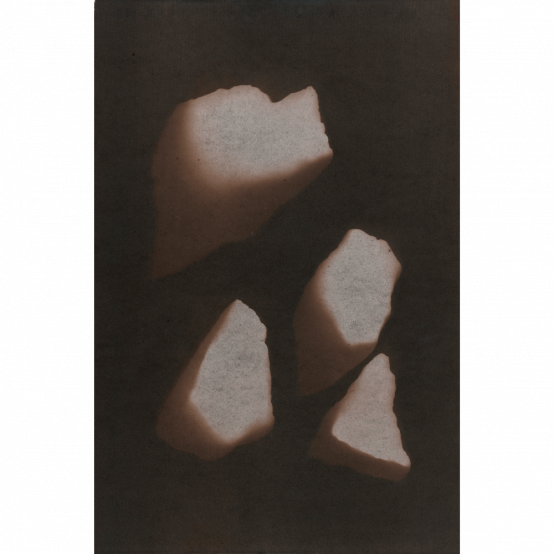

When I first became interested in cyanotype almost 10 years ago, Atkins' images were the first to appear in my searches. I was delighted to see a female figure in early photographic history and eventually started adding the hashtag #dearannaatkins to my Instagram account @ironsaltarchives as a tribute to her hard work. My first work for ed. art was released in 2015 and was an interpretation of the moon with a connection to the astronomical founder of the cyanotype. Now it seems appropriate that my collection of cyanotypes on display (some of which are also botanically tinted) should be named after the woman who actually developed his invention.

Cecilia Ömalm, Stockholm, autumn 2023